Introducing the Shell

Overview

Teaching: 20 min

Exercises: 10 minQuestions

What is a command shell and why would I use one?

How can I move around on my computer?

How can I see what files and directories I have?

How can I specify the location of a file or directory on my computer?

Objectives

Describe key reasons for learning shell.

Navigate your file system using the command line.

Access and read help files for

bashprograms and use help files to identify useful command options.Demonstrate the use of tab completion, and explain its advantages.

What is a shell and why should I care?

A shell is a computer program that presents a command line interface which allows you to control your computer using commands entered with a keyboard instead of controlling graphical user interfaces (GUIs) with a mouse/keyboard combination.

There are many reasons to learn about the shell.

- Many bioinformatics tools can only be used through a command line interface, or have extra capabilities in the command line version that are not available in the GUI. This is true, for example, of BLAST, which offers many advanced functions only accessible to users who know how to use a shell.

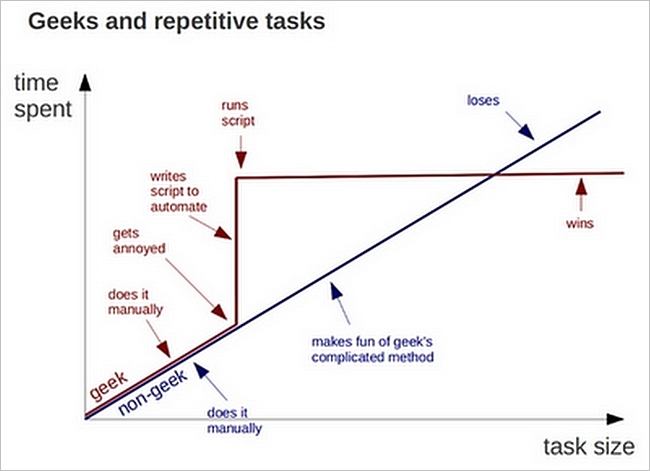

- The shell makes your work less boring. In bioinformatics you often need to do the same set of tasks with a large number of files. Learning the shell will allow you to automate those repetitive tasks and leave you free to do more exciting things.

- The shell makes your work less error-prone. When humans do the same thing a hundred different times (or even ten times), they’re likely to make a mistake. Your computer can do the same thing a thousand times with no mistakes.

- The shell makes your work more reproducible. When you carry out your work in the command-line (rather than a GUI), your computer keeps a record of every step that you’ve carried out, which you can use to re-do your work when you need to. It also gives you a way to communicate unambiguously what you’ve done, so that others can check your work or apply your process to new data.

- Many bioinformatic tasks require large amounts of computing power and can’t realistically be run on your own machine. These tasks are best performed using remote computers or cloud computing, which can only be accessed through a shell.

In this lesson you will learn how to use the command line interface to move around in your file system.

How to access the shell

On a Mac or Linux machine, you can access a shell through a program called Terminal, which is already available on your computer. If you’re using Windows, you’ll need to download a separate program to access the shell.

We will spend most of our time learning about the basics of the shell by manipulating some experimental data. Some of the data we’re going to be working with is quite large, and we’re also going to be using several bioinformatics packages in later lessons to work with this data. To avoid having to spend time downloading the data and downloading and installing all of the software, we’re going to be working with data on Hydra.

You can log-in to Hydra using the instructions here.

After loging on, you will see a screen showing something like this:

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

Welcome to the SI/HPC cluster Hydra-4 (Rocks 6.2/SideWinder, CentOS 6.9)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

This is one of the two login nodes.

+======================================================================+

| |

| You must change your password every 90 days. |

| Your account will be locked if it is inactive for 90+14 days, |

| read https://confluence.si.edu/display/HPC/Changing+your+password |

| |

+======================================================================+

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

May 16 2018

We are very pleased to announce that the systems administrator duties for

Hydra are being transferred to Dr. Jamal Uddin, who just joined the Research

Computing team at the Herndon Data Center (HDC). From now on he will be

responsible for administering and maintaining the HPC resources at HDC

(i.e. Hydra, full time).

We ask that you to submit HPC sys-admin related issues to SI-HPC-Admin@si.edu.

Bioinformatic/Genomics specific questions/requests should besend to

SI-HPC@si.edu, SAO users who need help for their applications should contact

Sylvain at hpc@cfa.harvard.edu.

Reminders:

+ An interactive queue has been added to Hydra, interactive use of the

login nodes is being monitored.

+ All public disks (/pool and /scratch only) are scrubbed. Reasonable

requests to restore scrubbed files must be sent no later than the

Friday following the scrubbing, by 5pm.

+ Two test queues are available:

- uTSSD.tq - allows use of a local SSD for jobs performing heavy I/Os,

- uTGPU.tq - allows use of a GPU for code built with GPU capability,

Please contact us if you'd like to use either.

This provides a lot of information about the remote server that you’re logging in to. We’re not going to use most of this information for

our workshop, so you can clear your screen using the clear command.

$ clear

This will scroll your screen down to give you a fresh screen and will make it easier to read. You haven’t lost any of the information on your screen. If you scroll up, you can see everything that has been output to your screen up until this point.

Navigating your file system

The part of the operating system responsible for managing files and directories is called the file system. It organizes our data into files, which hold information, and directories (also called “folders”), which hold files or other directories.

Several commands are frequently used to create, inspect, rename, and delete files and directories.

Preparation Magic

If you type the command:

PS1='$ 'into your shell, followed by pressing the Enter key, your window should look like our example in this lesson.

This isn’t necessary to follow along (in fact, your prompt may have other helpful information you want to know about). This is up to you!

$

The dollar sign is a prompt, which shows us that the shell is waiting for input; your shell may use a different character as a prompt and may add information before the prompt. When typing commands, either from these lessons or from other sources, do not type the prompt, only the commands that follow it.

Let’s find out where we are by running a command called pwd

(which stands for “print working directory”).

At any moment, our current working directory

is our current default directory,

i.e.,

the directory that the computer assumes we want to run commands in

unless we explicitly specify something else.

Here,

the computer’s response is /home/username,

which is your home directory:

$ pwd

/home/username

Let’s look at how our file system is organized.

On Hydra, we ask that users run jobs from their /pool, /scratch, or /data directories (e.g. /pool/genomics/username).

We will be using files located in /data/genomics/workshops/data_carpentry_genomics

You can copy the files to your space by first navigating to your /pool/genomics or /pool/biology directory (e.g. /pool/genomics/dikowr)

The command to change locations in our file system is cd followed by a

directory name to change our working directory.

cd stands for “change directory”.

and then using cp -r, which stands for copy recursively (i.e. the whole directory).

cd /pool/genomics/username

cp -r /data/genomics/workshops/data_carpentry_genomics/dc_sample_data .

We’ll be working with these subdirectories throughout this workshop.

Let’s say we want to navigate to the dc_sample_data directory we saw above. We can

use the following command to get there:

$ cd dc_sample_data

We can see files and subdirectories are in this directory by running ls,

which stands for “listing”:

$ ls

sra_metadata untrimmed_fastq

ls prints the names of the files and directories in the current directory in

alphabetical order,

arranged neatly into columns.

We can make its output more comprehensible by using the flag -F,

which tells ls to add a trailing / to the names of directories:

$ ls -F

sra_metadata/ untrimmed_fastq/

Anything with a “/” after it is a directory. Things with a “*” after them are programs. If there are no decorations, it’s a file.

ls has lots of other options. To find out what they are, we can type:

$ man ls

Some manual files are very long. You can scroll through the file using your keyboard’s down arrow or use the Space key to go forward one page and the b key to go backwards one page. When you are done reading, hit q to quit.

Challenge

Use the

-loption for thelscommand to display more information for each item in the directory. What is one piece of additional information this long format gives you that you don’t see with the barelscommand?Solution

$ ls -ldrwxr-x--- 2 username username 4096 Jul 30 2015 sra_metadata drwxr-xr-x 2 username username 4096 Jul 30 2015 untrimmed_fastqThe additional information given includes the name of the owner of the file, when the file was last modified, and whether the current user has permission to read and write to the file.

No one can possibly learn all of these arguments, that’s why the manual page is for. You can (and should) refer to the manual page or other help files as needed.

Let’s go into the untrimmed_fastq directory and see what is in there.

$ cd untrimmed_fastq

$ ls -F

SRR097977.fastq SRR098026.fastq

This directory contains two files with .fastq extensions. FASTQ is a format

for storing information about sequencing reads and their quality.

We will be learning more about FASTQ files in a later lesson.

Shortcut: Tab Completion

Typing out file or directory names can waste a lot of time and it’s easy to make typing mistakes. Instead we can use tab complete as a shortcut. When you start typing out the name of a directory or file, then hit the Tab key, the shell will try to fill in the rest of the directory or file name.

Return to your home directory:

cd /pool/genomics/username

then enter:

$ cd dc_sam<tab>

The shell will fill in the rest of the directory name for

dc_sample_data.

Now change directories to untrimmed_fastq in dc_sample_data

$ cd dc_sample_data

$ cd untrimmed_fastq

Using tab complete can be very helpful. However, it will only autocomplete a file or directory name if you’ve typed enough characters to provide a unique identifier for the file or directory you are trying to access.

If we navigate back to our untrimmed_fastq directory and try to access one

of our sample files:

$ cd /pool/genomics/username

$ cd dc_sample_data

$ cd untrimmed_fastq

$ ls SR<tab>

The shell auto-completes your command to SRR09, because all file names in

the directory begin with this prefix. When you hit

Tab again, the shell will list the possible choices.

$ ls SRR09<tab><tab>

SRR097977.fastq SRR098026.fastq

Tab completion can also fill in the names of programs, which can be useful if you remember the begining of a program name.

$ pw<tab><tab>

pwd pwd_mkdb pwhich pwhich5.16 pwhich5.18 pwpolicy

Displays the name of every program that starts with pw.

Summary

We now know how to move around our file system using the command line. This gives us an advantage over interacting with the file system through a GUI as it allows us to work on a remote server, carry out the same set of operations on a large number of files quickly, and opens up many opportunities for using bioinformatics software that is only available in command line versions.

In the next few episodes, we’ll be expanding on these skills and seeing how using the command line shell enables us to make our workflow more efficient and reproducible.

Key Points

The shell gives you the ability to work more efficiently by using keyboard commands rather than a GUI.

Useful commands for navigating your file system include:

ls,pwd, andcd.Most commands take options (flags) which begin with a

-.Tab completion can reduce errors from mistyping and make work more efficient in the shell.